Living Our Beliefs: Exploring Faith & Religion in Daily Life

Religion and faith are important for millions of people worldwide. While ancient traditions can provide important beliefs and values for life, it can be hard to apply them to our lives today. And yet, weaving them into our days can bring benefits––greater meaning in life, more alignment between our beliefs and our actions, and deeper personal connection to our faith and each other.

In Living Our Beliefs, we delve into where and how Jews, Christians, and Muslims express their faith each day––at work, at home, and in public––so that we can see the familiar and unfamiliar in new ways. Learning from other religions and denominations invites us to notice similarities and differences. Comparing beliefs and practices prompts us to be more curious and open to other people, reducing the natural challenge of encountering the Other. Every person’s life and religious practice is unique. Join us on this journey of discovery and reflection.

Starter episodes with Jews:

Mikveh: Reclaiming an Ancient Jewish Ritual – Haviva Ner-David

Honoring and Challenging Jewish Orthodoxy – Dr. Lindsay Simmonds

The Interfaith Green Sabbath Project – Jonathan Schorsch

Starter episodes with Christians:

Is a Loving God in the Brokenness and Darkness? – Will Berry

Queering Contemplation and Finding a Home in Christianity – Cassidy Hall

Embodying the Christian Faith: Tattoos and Pilgrimage – Mookie Manalili

Starter episodes with Muslims:

Religious Pluralism v. White Supremacy in America Today – Wajahat Ali

How to be Visibly Muslim in the US Government – Fatima Pashaei

Bonus. Understanding the American Muslim Experience (Dr. Amir Hussain)

Living Our Beliefs: Exploring Faith & Religion in Daily Life

Bonus. Understanding the American Muslim Experience (Dr. Amir Hussain)

Episode 62.

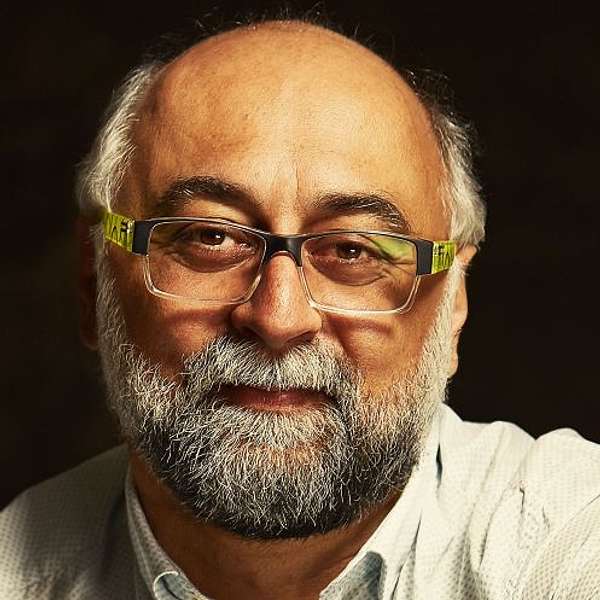

Esteemed scholar Dr. Amir Hussain, Professor of Theological Studies at Loyola Marymount University (Los Angeles), author of five books, and immediate past President of the American Academy of Religion (AAR) joins me for a lively discussion of the contemporary Muslim experience in North America. Despite the presence of Muslims arrived in the US in the first slave ships, the long history of participation in American society has gone unnoticed and unappreciated. Certainly, since the September 11 terrorist attack and now again with the war in Gaza, Muslims have been subject to harassment and Islamophobia. Many such acts of hate are motivated by inaccurate and misguided assumptions about Muslims, who they are and what they believe. The day-to-day life is not all bad nor is it the same in every place. Amir and I cover these and other topic in this engaging conversation.

Highlights:

· Diversity within American Islam, including ethnic and sectarian differences

· Cooperation and understanding between different religious groups in the U.S.

· Stereotypes within the Muslim and Jewish communities

· Coexistence, integration, and blending into society for minority communities

· Misperceptions about Islam and Muslims

· Importance of education in changing perceptions and the need for diverse Muslim representation

Social Media links for Amir:

Loyola Marymount University – http://faculty.lmu.edu/amirhussain/

American Academy of Religion (AAR), Immediate Past President – American Academy of Religion

Social Media links for Méli:

Talking with God Project – https://www.talkingwithgodproject.org

LinkedIn – https://www.linkedin.com/in/melisolomon/

Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100066435622271

Transcript: https://www.talkingwithgodproject.org/podcast-1/episode/7f3bd8f1/bonus-understanding-the-american-muslim-experience-dr-amir-hussain

Follow the podcast!

The Living Our Beliefs podcast offers a place to learn about other religions and faith practices. When you hear about how observant Christians, Jews and Muslims live their faith, new ideas and questions arise: Is your way similar or different? Is there an idea or practice that you want to explore? Understanding how other people live opens your mind and heart to new people you meet.

Comments? Questions? Email Méli at – info@talkingwithgodproject.org

The Living Our Beliefs podcast is part of the Talking with God Project.

Dr. Amir Hussain transcript

Understanding the American Muslims Experience

Meli [00:00:05]:

Hello and welcome to Living Our Beliefs, a home for open conversations with fellow Christians, Jews, and Muslims. Through personal stories and reflection, we will explore how our religious traditions show up in daily life. I am your host, Meili Solomon. So glad you could join us. This podcast is part of my Talking with God Project. To learn more about that research and invite me to give a talk or workshop, go to my website, www.talkingwithgodproject.org. This is episode 62 and is a bonus episode where we address a topic rather than a personal faith path. My guest today is Dr. Amir Hussain. We will be exploring the contemporary Muslim experience in North America. Amir, a Canadian Muslim, is Professor of Theological Studies at Loyola Marymount University, the Jesuit University in Los Angeles, where he teaches courses on religion. His specialty is the study of Islam, focusing on contemporary Muslim societies in North America. His university and postgraduate academic degrees are all from the University of Toronto. He is the immediate past President of the American Academy of Religion and has published widely. He was even an advisor for the television series The Story of God with Morgan Freeman and appears regularly on other shows. Amir lives in Los Angeles with his family. His social media links are listed in the show notes. Hello, Amir. Welcome to my Living Our Beliefs podcast. I'm really pleased to have you on today.

Amir [00:02:07]:

Real pleasure to be with you. Thank you for having me on the show.

Meli [00:02:10]:

This is a bonus episode, which means that we will be focusing on a topic rather than your personal faith path. That said, I do like to begin with my usual first question. What is your religious and cultural identity?

Amir [00:02:26]:

So I am a Sunni Muslim. I was born in Pakistan, so I'm South Asian. Came to Canada when I was a kid, so grew up in Canada, working class. And so, it's one of the most complicated things, but Sunni Muslim, South Asian, working-class Canadian who's lived in the US for 25 years.

Meli [00:02:47]:

We're going to talk today about the story of American Muslims. Given your heritage, that might also include Canadians, but as I understand, your research has been more on American than Canadian.

Amir [00:03:03]:

Yes. The last 25 years, I've been working on Islam in America. I think there's some interesting differences between Canada and the US, and we can talk about that if you want.

Meli [00:03:14]:

Okay. Great. So with that as the focus, I'd like to begin by simply setting the scene really around the numbers and the percentages. One of the things that I, as an American Jew, am always very aware of is that the perceptions and misperceptions of any given population can really feed a misunderstanding of how big that population actually is. So I think that would be a good place to start.

Amir [00:03:54]:

I think, absolutely, that that's a great, point. I live in Los Angeles, and my students think there's 50million or 100million Jews in the world because there's such a large Jewish population They're amazed because they think it's a much higher percentage. So American Muslims, we don't have a accurate count. This is one of those differences between, the Canadian scene and the American scene. In Canada, we actually asked the question of religious affiliation on the census in its sort of standard form. And so the last household census counted over a million Muslims in Canada. We used to ask that question here on the US Census. We don't ask it anymore, except in certain cases, so we have to extrapolate and project. I've seen estimates of the American Muslim community that are as low as about 3 ½ million, which I think is way too low. I've seen estimates that say there's 10 to 12million, which I think is way too high. My own sense as a researcher who's worked on this, who can do things like saying, okay. We know there's this many Pakistanis. We know that 95% of Pakistanis are Muslim. You know, perhaps a greater percent of Christians have come here, but, you know, what are the numbers there? My own best sense is there's at least 6million American Muslims. There may be as many as 7million. So somewhere between 6 and 7million. And that that's the number. It's it's not unique to me. It's, most of us working on Islam in America will come up with that figure, which ballpark is close to the number of Jews in the US. You know, the the the numbers of Jews I've seen are are, again, around 6, 7 million in the United States. And so that's just in terms of a basic number. You know, you're looking at about 6 million American Muslims. If you look at the breakdown of that, it's really fascinating. Again, we don't have exact numbers on this, but at least a quarter of us, and I say that as someone who's American Muslim, are African American. People who have no doubt about their Americanness, who've been Americans for literally 100 of of years, you know, going back to the transatlantic slave trade. So at least a quarter of us are African American. The largest is probably my community, South Asians, you know, which isn't surprising. The countries with the most Muslims are South or Southeast Asian countries, you know, Indonesia, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh. Those countries have about half the Muslims in the world are in those four countries. So it's no surprise that South Asians, people from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, make up a little over a third. So about 25% African American, about 35% South Asian. The other big group are Middle Easterners. And, again, same kind of diversity. By Middle Eastern, do you mean, you know, someone from, Egypt, someone from Syria, someone from Lebanon? About a third. Again, about 30, 35% are Middle Eastern. But that could also mean, in the case here in Los Angeles, Iranians. You know, Iranians are Middle Eastern, except, of course, they're not Arabs. You know, Turkey sometimes gets counted in the Middle East, sometimes it doesn't. And so, you know, by Middle Eastern, do you mean Arabs? Do you mean Turks? Do you mean Iranians? So about a third are Middle Eastern. And then you have really interesting numbers of white American Muslims. Here in Los Angeles, this really interesting phenomenon of Latino Muslims, Southeast Asian Muslims, like, in in, Santa Ana, couple of hours south of where I am in Los Angeles. You have this fascinating community of Cham Muslims at Cham, the people from this historical, area near Cambodia and Vietnam who historically were Muslim and then came over after the the Vietnam War. And so those are things you you don't expect to see South Asian, you know, people from Cambodia, Vietnam and say, hey. I bet those folks are Muslim. Well, some of those folks are Muslim.

Meli [00:07:47]:

Wow. Thank you. That it really opens and corrects the the sense of who's in the picture.

Amir [00:07:55]:

No. Absolutely. And when people say, you know, that person looks like they're they're Muslim, you know, you wanna say, well, what does that mean? Does that mean this African American person? Does this mean someone like me who's South Asian? Does this mean someone who's Latino? Like, one of my friends, the the imam for the Latino Muslim community here in Los Angeles, this guy named Ceasar Dominguez, who was born in Mexico City. If Ceasar and I are walking down the street, people aren't gonna point to him and go, hey, I bet that guy from Mexico City named Ceasar Dominguez is a Muslim. Well, he's a Muslim.

Meli [00:08:26]:

Was he raised in that, or did he convert?

Amir [00:08:29]:

He he converted. And and that's one of those interesting moments, not to tell his particular story, but he was fascinated with Egypt. And so as a kid, wanted to know about the pyramids and the pharaohs and this kind of thing and ended up going to Egypt, not for any Islamic thing, but because of the fascination with Egypt. And I think when he was there, sort of fell in love with the culture, fell in love with the religion, became a a Muslim. So it's a very different kind of root there, but but you have growing number of converts to Islam, especially here in the North American setting.

Meli [00:08:59]:

Yeah. I was just gonna ask you that because my my understanding is that an awful lot of the African American, that 25% African American of the Muslim population are converts.

Amir [00:09:12]:

Absolutely. And so what what you have here is this funny kind of history where the first documented Muslim that we have coming to what is now America is a slave of one of the Spanish conquistadors, Estevanico, Little Stephen, you know, the Moor, comes in 1528. So we're coming up on 500 years where we know there was someone who supposedly came in through what is now Florida, ends up going through what is now Texas. So if you go, for example, to the state capital in Texas, in Austin, you will see the Texas African American Historical Monument. And it has it's this big monument that's there on the grounds of this of the state house in Austin. And there's a image of, you know, what we think Estevanico's little Stephen the Moor looked like. And so he's there because he's like the first person of African descent to come into what is now Texas. He's a Muslim slave. So on the one hand, you have this history that goes back 500 years. But because of slavery, because of, you know, Islam being something that was not just marginalized but prohibited, the slaves becoming Christian, taking on the names of their slave owners, all that kind of thing, you see this dying out of Islam. It's really in the 20th century with this heterodox movement, the Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm x, that you have Islam being sort of reintroduced here. And then in the fifties sixties, so many, African American folks who come through the Nation of Islam. The Nation of Islam goes through its own process and becomes sort of mainstream, Sunni Islam there. But, absolutely, you have that sense of conversion. Often in the community, it's spoken of not as as conversion, but reversion. You know? And it it's 2 things.1 is a a theological message, you know, that this notion that God creates human beings with their the proper religious orientation. It's the parents who make them, you know, Muslims, Christians, Jews there. But this sense that you're reverting back to your original self. And then the historical thing that you may well have been a Muslim. We know that at least 10% of the slaves brought over from West Africa were Muslim. You know, that surprised me when I watched the first iteration of Alex Haley's Roots, you know, with LeVar Burton as Kunta Kinte and this moment is a, you know, adolescent watching my television screen. Like, wait, Kunta Kinte is a Muslim? There were Muslim slaves in America? And you guys, well, of course, of course, Islam has been in West Africa, you know, since 9th century. Of course, if you'd brought slaves over from West Africa, some of them would have happened to be Muslim. And so you have this history, you know, going back 500 years of being an African American Muslim, but only in the present that sense of, oh, yeah. We didn't know our ancestry. We didn't know our tribe. We didn't know our people. We didn't know our our language. And so, you know, how do you learn that, oh, we actually came from what is now Ghana, or we actually came from what is now, Mali, or or, you know, those kinds of places.

Meli [00:12:10]:

Yeah. Yeah. And talking this through is such a reminder that the world is really complex this way. You know, the religious and cultural mixing and melding is just the fact of our world, and certainly over the last 100 of years is increasingly so. What I then wonder about is what does that statement mean for today? You know, what does that mean for being a Muslim who is African American, or from South Asia, or from the Middle East? What does your research say about the experience?

Amir [00:12:55]:

Yeah. It it's really fascinating to see the kinds of ways in which American Islam is this unique kind of thing. And part of it, exactly as you said, is is that mixing, first of all. So if you look at just ethnic racial diversity, the 2 most religiously diverse congregations in America, according to the the Pew Research Forum, are American Muslims and Seventh day Adventists. You know, this really interesting, interesting kind of thing here. So if you go to a local mosque, it may be an ethnic mosque. It may be, you know, this is a Turkish mosque and the people there are Turkish, or this is a Pakistani mosque and most people are from Pakistan. But other places, you know, you have people who are South Asian, people who are Middle Eastern, people who are African American. And so those connections, like, at my university, we have a number of international students who are Muslim who come from primarily, Kuwait, from the Gulf, you know, Saudi, the Emirates. And oftentimes for them, it's their first moment interacting with a Muslim like me who's South Asian, a Muslim who's African American, a Muslim who's comes from a Chinese background. The sectarian differences, we can get into that as well. You know, the majority of the world's Muslims are Sunni Muslims. I happen to be a a Sunni Muslim. About 80, 85 percent of the world's Muslims are Sunni Muslims. About 15, 20% are Shia Muslims. Now in America, you have about 30% of American Muslims being Shia Muslims. That's because of immigration. Again, I live here in Los Angeles. A lot of Iranian Muslims, almost all the Iranian Muslims, you know, are are Shia Muslims. The Lebanese Muslims, folks from there, from Iraq. And so the fact that in America, you have approximately double the number of Shia Muslims that you have sort of worldwide, you know, you have these really interesting movements within Islam that can sort of flourish here because one of the great things about America, you know, the First Amendment is, you know, nothing prohibiting the free exercise of religion. And so a group like the Ahmadiyya community that comes out of, India, Pakistan, that by other Muslims is seen not just as as heterodox, but as un Islamic because they believe that that their figure, Mercifulullah Muhammad, which is who they're named after, is a a figure after the prophet Muhammad. And for Muslims, the idea is no, no, no, no, no, that there's no prophet after Muhammad. You can call other people reformers, absolutely, but there's prophecy ends with Muhammad. With the Ahmadiyya, it's a little bit different. And so in Pakistan, where I come from, they're officially discriminated against. You know, you cannot call yourself a Muslim if you're Ahmadiyya in Pakistan. They've built one of the largest mosques in America here. That's a great example where you have these sort of heterodox kinds of movements. The Ismaili community, again, a very small, sort of community, maybe 15million Muslims coming out of the tradition of 7, imams as distinct from the Iranian ones. That experience of being a Muslim in America is very different than if you're a Muslim growing up in Pakistan, where, you know, almost all the other people you see are Sunni Muslims and you look at the Shia Muslims with some, you know, disregard there. Here, it's a really fascinating moment where, you know, I've prayed side by side with Shia Muslims. You know? I remember, being at the University of Toronto and being at the, you know, Friday prayers we took the university, and there wasn't a full-time imam there. And oftentimes, one of the people that would lead the prayers would be this guy that came from a Shia community who's leading a prayer composed mostly of Sunnis. You know? That wouldn't happen in other parts of the Muslim world where you have the the real sectarian violence between Sunnis and Shias here. So I think that that sense of those differences. And then you layer on all the kinds of issues that come up here. You know, what I mean by that is the sort of issues of Western modernity, gay marriage, same sex relationships, you know, all those kinds of things where you had the president of Iran very famously saying there was no gay people in Iran. Well, that's ridiculous. Of course, there are gay people in Iran. You know? What do you do when you have, the criminalization of this? You know, in certain parts of the Muslim world, homosexuality is criminal. You will go to jail if you're caught. What do you do in America? We're not only will you not go to jail, but you're legally able to be married, to adopt children, all those kind of things, which means that you have to deal with this in a religious way, you know, in a way that you don't in in other places. And so you have that huge diversity. You have Muslims who are open to, same sex marriage. Muslims celebrate that. And Muslims who think this is evil. How can we do this kind of thing? We must stop this. And you see these alliances, you know, between conservative religious groups. So, for example, here in California, a couple of years ago, the sort of moves to diminish, gay marriage were led by a couple of religious groups, but they were conservative Muslims, conservative Latter day Saints, conservative Catholics. It's like, this is kind of fascinating that folks who probably wouldn't see eye to eye religiously on certain things, all of a sudden they're gonna work together because they believe, you know, certain things about sexuality, certain things about gender. But all this to say that, you know, you have to deal with those kinds of issues of Western Modernity here in America that you don't have to deal with in the country of origin.

Meli [00:18:16]:

Yeah. I'm hearing how the religious and cultural percentages, the balances of the population are then interacting with the social issues, the the concerns, and the priorities of where people are living really makes sense to to lean a bit into theory. I'm wondering about the relationship between violence, so sectarian violence, interreligious violence, and the predominance of a sect in a situation versus a more heterodox situation.

Amir [00:18:56]:

Yeah. And and as usual, it's a complicated picture. So let me start with, you know, the the country I came from, Pakistan, where you have a majority Sunni community, a minority Shia community, a minority Christian community. And, unfortunately, you see discrimination, you know, against both the Christian communities and the Shia, communities in Pakistan. You know, I think that's where here in the US, you're able to do really powerful kinds of things to say, hey, look. There's nothing in the Islamic tradition that says Sunnis and Shias have to be violent towards each other. There's been a history of that. There's no question of that. So, for example, in 2003, just before the Iraq war started, we knew what was gonna happen in the sense that you've got in Iraq ethnic differences between Kurds and Arabs and religious differences between, Sunnis and Shias there. And you've got a significant Shia population in Iraq. You knew there'd be that kind of sectarian violence. And so what you had were leaders of Shia centers here, particularly Imam Qazwini, you know, who was the the head of probably the largest, Shia center in in the West Coast. And then, Hassan and Maher Hatut, the Hatut brothers who Egyptians who set up the Islamic Center of Southern California. And there's there's the 3 of them, you know, 2 Egyptian, Sunnis, 1 Shia saying, look, we're able to worship it. We're able to work here. There's nothing in our traditions that calls for this. There were conflicts in, Egypt, you know, between the the Sunni Muslim population and the Coptic Orthodox Christian population, including, unfortunately, some horrific violence done by Sunnis to the Orthodox, to the cops. Well, you had the bishop of Saint Mark's, this Coptic Orthodox Church with doctor Hatut, the leader of this Islamic Sunni organization, coming together and saying, look, here we are, 1 Egyptian Coptic, 1 Egyptian Muslim. There's nothing in our traditions that say we have to be violent to each other, do this kind of thing. And so in a funny way, and I don't mean to sound pollyannaish about this, but, you know, this is one of the ways that American Muslims can help in the rest of the world to say, look at our example here. We get along just fine with our Christian neighbors, with our Jewish neighbors. We don't need to have this violence between, Sunnis and Shias. We don't need to have this violence towards, you know, Christian minorities here. I think that becomes a a really powerful thing that we, meaning American Muslims, are able to contribute to the global Muslim world.

Meli [00:21:31]:

Yeah. Absolutely. So what is it? What is or what are the ingredients that support increased cooperation and understanding as you see it?

Amir [00:21:45]:

I think part of it is just the that living together, that they come together. And so, for example, I mentioned that many of our Muslim students at my university are international students from Kuwait, from Saudi Arabia, from the Gulf. Oftentimes, the first time they've met someone who's Jewish is here at the university. You know? When we opened up our prayer space, and we now have a dedicated prayer space for our our Muslim students, We do Friday prayer. We had maybe, 25 people at prayer on Friday, which doesn't sound like a lot, but we have about 250 Muslim students on campus. So that's 10% of our Muslim students, you know, who are there. But when we open that prayer space, the first person that that spoke was our campus rabbi, you know, Rabbi Zach Seisman. The second person that spoke was one of our Jesuits, father, Alan Deck. Then we had the sort of guest of mom come in. And so where I'm going with this is that you need to have those kinds of connections. It's easy to demonize the Jews if you've never met a Jew, if you've never interacted with someone that that's Jewish. And to bring those communities together for the the Sunni students, oftentimes for the first time to say, oh, you're someone that's a Shia. You're someone that's completely different. And in my country, I may have been told that, you know, these horrible things about you. But now that I get to know you, it's it's a different interpretation of of Islam. It's different than what I do, but it's not this completely heretical thing that I've been, taught. And so so I think, again, it's it's it's that coexistence, but it's also the education part of it. You you can't just assume that if you have people of different backgrounds coming together, that they will then work together. You then have to do some program. You then have to do some work to bring them together. So they're not just simply, you know, the the Sunni Muslim kids are sitting over here, and the Shia kids are sitting over there, and they're not interacting at all with the the Jewish kids or the Christian kids. You know, how do you bring them together? What what do you do? And I think that becomes really important.

Meli [00:23:46]:

Yeah. Thank you for that, and thanks for noting that education is part of it. And I agree with the coexistence part. Absolutely. The caveat, the damper on that really comes from Germany pre-Hitler. There was a big Jewish population definitely in Berlin, which to this day is the biggest Jewish population in Germany, huge in Poland, and very integrated. You know? They served in the wars. They were professionals and laborers and everything, and yet they were completely decimated. So what I'm now wondering is it seems that coexistence is not sufficient, and that education at a university level or adult ed, whatever it is, is is important. I'm wondering about the effect of a valid expression of your religion and and really owning it. You know? I wonder if part of what occurred in Germany was that the Jews were so integrated and really not not showing not well, that's not totally true because they would have stars of David on their win on their shop windows. But I'm wondering about this relationship between your observance level, your showing of your religion, your expression of your religion, how much your neighbors and colleagues understand about your culture and religion, the percentage of your group in the larger population, and, of course, you know, other larger exacerbating issues like what was happening pre World War 2 in Germany. So, you know, maybe it's just a whole mix. What do you think?

Amir [00:25:40]:

Well, I I think you're absolutely right. There's so many factors going on. If you look at the the German example, which I think is is a really, really good one. And so precisely this, you have this history of antisemitism, first of all, built into Christianity, you know, from its its beginnings. Like, I teach at a Catholic university. It really wasn't until 58 years ago, 1960 5, with the 2nd Vatican Council, that the church really changed, you know, its position vis a vis the Jewish community. Before that, the Good Friday sermon was very much about the evils of the Jews who had murdered Christ, you know. And so so so I think, you know, in the German case, you're dealing with that. Part of it is also as a minority who's successful. You know, what do you do when those class kind of things I identified myself as someone working class, you know, haven't been working class for decades, very comfortably, you know, middle class as an academic, but I still identify there. And so, you always think about those kinds of issues. Is it this question about, well, look at them over there, they've got the wealth, they've got I mean, those kind of stereotypes that you see in really interesting ways about Jews can also be about Muslims. Like, I was involved about a decade ago, Susanna Heschel, this marvelous, marvelous scholar, you know, who's the daughter of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. She invited me to this conference she was doing at Oxford on antisemitism and Islamophobia. And these really interesting moments of, yeah, the trope, not just in the Middle Ages, but, you know, in the last century of the Arab and the Jew were synonymous. You know, the greedy Arab, the greedy Jew, the hook-nosed foreigner, Semite who doesn't really fit in society, who's lecherous, you know, really interesting how those are are developed. But I think in that German case, you know, when you have the economic kind of thing and you're a minority and it's really easy to pick on minorities, really say, hey, you know why we're suffering? Because them over there, look at what they're doing and let's, you know, do that. And I think, again, that that moment of how are people able to do this with with their neighbors? You know, the the same thing happening in the Balkans, where you have Bosnians, Serbians, Muslims, you know, Orthodox, Christians, Catholic Christians, and Muslims who are living in what seems to be harmony. And then when it happens, it happens, and then you have people stoking these fears. And it's really easy to cross over into that. And so I think, absolutely, you have to have that kind of of coexistence, but you also have to have that cooperation. So I think sometimes, you know, that that moment of, are we a distinct community? Do we blend in? And and, you know, you look at the the real change in Judaism that happened precisely in that German European context. Do we need to speak Hebrew? Can we speak German? Can we have music that's like the German music? Can we eat the food? I think pork is one of the 4 food groups in Germany. You know, as a Muslim, as a Jew, you can't do that. Can you do this? Can you eat shrimp? Can you do that? You know, at what level you're willing to accommodate into this society? And at what level is there a sense that, yeah, as much as you do that, you're never going to fit in. And I think that's one of those those differences. And not not to change topics, but in a very different way. When the, Unite the Right happened in Charlottesville, and you had those sort of horrific images. And I I wanna be very careful. What bothered me the most wasn't the Jews wanna replace us. I'm I'm not saying that because I'm anti Semitic. I'm not I'm not. But, you know, we've we've heard those chants before in America around, antisemitism, that kind of thing. What bothered me the most was the blood and soil chants because, again, that's one of those differences. Part of the thing about Americans, it doesn't matter who your father was. You can come to this country. This is a land of new beginnings. You can be whoever you are, and it doesn't depend on in the country of origin because you were this or because you were that or because you didn't have this education. You're never gonna move beyond here. You can do it in America. That's not the case in Europe. You know? You can be a guest worker in Germany as a Turk. You're never gonna be a German citizen even if you're born there, even if your kids are born there. And so that that sense of, you know, are you really part of this this soil, of this lineage, of this bloodline. I think that's part of the the difference there. And and, again, I I don't mean this to be, you know, hopeful, but I'm an educator, and you have to be hopeful if you're an educator. You know? And and you hope that it's that that's one of those those differences here. You know, that for us in America, we can make those kinds of changes. Now doesn't mean you don't see those horrific things. And I and I remind my Muslim students all the time with all the increases in Islamophobia, especially post-9/11, far and away, like, every year, over half of the hate crimes against religious group are against Jews. People who've been here for centuries. And so it it tells us, you know, the the work we still need to do. Jews are very well integrated into American society, much more so than Muslims. If you look at the number of Muslim judges, lawyers, politicians as compared to to Jewish ones. You have that history. And yet you still have over half the hate crimes against a religion are against Jews.

Meli [00:30:53]:

One of the things that I wonder about is this question of, are we we Jews hated because we're punching above our weight? And what do you see regarding Islamophobia and the Muslim community?

Amir [00:31:08]:

So I think you see a couple of things there. Part of it is that sense of, you know, if you don't know someone that that's a Muslim, it's easy to have this idea that Muslims are violent. Like, I was just I'm not gonna name the the person of the book. I was asked, as I often am, to, you know, look look at a book manuscript and see if I'd be willing to give an endorsement of it. And this was someone talking about world religions and violence in Islam and then throwing in a line, you know, well, but Christians were violent up until the Crusades. I'm like, wait, you're saying that Christians stopped being violent after the Crusades? Like, think about what we just talked about, the Holocaust. Think about what we just talked about, the Balkans. Think about the murders in in this country around Christian nationalism and the hate there. And so that misperception, oh, you see what's happening there in the Muslim world. You see this kind of that's who Muslims are. That's what Muslims do. And so I think that kind of thing can be really problematic, like, if you don't know a Muslim and what you see is the violence. You know, if the images aren't the positive kinds of images, I say there's someone, like I said, lives and works in Los Angeles. We're the capital of of the image that puts that image out there, not just for Americans, but for the rest of the world, that that's American culture. American culture is not just consumed in America. It's all over the world. I had a student a couple of years ago in my Islamic America class. I did this great presentation where he starts by putting up a slide of, Ahmed Zwehl. If he was a chemist at CalTech, he'd won a Nobel Prize. Anyone know who this is? No clue. No one who this was. Then he puts up a slide of Bin Laden. Everyone knew who Bin Laden was. And it's just that kind of notion that, you know, if the Muslim you can identify is the terrorist, if the Muslim you see on TV is the terrorist, do you recognize the Muslim that's the Nobel Prize winner in chemistry? And in a funny way, I don't I don't mean this as another connection, but I think there's really interesting connections between the American Muslim community and the American Jewish community. It's this sort of, you know, you know they're Jewish. Right? We do the exact same thing. You know, they're Muslim. Right? You know, that person, he's actually a Muslim. You know, that guy that owns the Jacksonville Jaguars? He's actually a Muslim. So here you got a Muslim who's, you know, literally in the 1%. What is a Muslim guy who's a pro sports owner? Is that who you think of when you think of Islam, or is it the terrorists? And so I think some of it is that. Some of it, again, is that convenient kind of if you're a minority. You can say, you know, here's the issue. Here's the problem. You know, the reason our country is not doing well is is because of this group. That's not the case. You know, American Muslims, we're we're we're we're this interesting bimodal distribution. What I mean by that is, you know, 25% of us are not the 1%, but at least the top 10%. You know, people like me who are doctors, lawyers, engineers whose salaries are, you know, in in the top, percentage. Now, a little more than that, at least 30% of us are working class, people who live below the poverty level. You know, we don't think about that when we think about Muslims. And, again, it's funny as I've seen this out loud. Same thing with the Jewish community, that stereotype of, like, all Jews are rich and successful and wealthy. We have lots of wealthy and successful Jews who are doctors, lawyers, but you also have working class Jews, immigrant Jews, people who are just getting by, and we don't think about that. Same thing in the Muslim community there. Look what's happening literally as as we're speaking. The kinds of stuff happening with the violence in the Middle East, with the Houthis in Yemen, with the, attack that killed Americans in in Jordan, with the response in Iraq. And it's like, okay. Are are we gonna get pulled into this another cycle of things happening in the Middle East? And guess what? Those folks tend to be overwhelmingly, Muslim. And so if you're worn parts of the Muslim world, you forget that folks here are Americans who are on the side of America. 9/11, when that happened, this idea that because it was 19 Muslims that that killed 3,000 Americans, including, by the way, many Muslim Americans, that somehow American Muslims were with the terrorists and not with Americans. I think that that's the kind of negative sorts of images that that get put out there.

Meli [00:35:21]:

Yeah. Absolutely. In all of these examples, what really stands out for me is a reminder that that desire to say, we are the victims, you are the terrorist, is really a desire to have more of a black and white kind of image of the world and to feel secure in your identity and your in your place. If that's really the human inclination, really then the question that is begging is, what the heck do we do about that? Because that seems really hardwired.

Amir [00:36:04]:

Absolutely. And I think one of the things we can do with this education, whether you're talking about education at the elementary level, the secondary level, or what I do at the university level, making those kinds of connections. But, also, part of it is is the education that we're doing right here. The people that are listening to this podcast, that are listening to you clearly have this desire to learn. I think people have a great desire to learn about the world. I think human beings have that. We all know the curiosity of children. I don't think we lose that. The question becomes, how do we do it in the midst of all our time, in the midst of everything there? Am I gonna, you know, go take a extension course in my university? You know, I don't have time for that. But I can listen to the Living Our Beliefs podcast, you know, as I'm driving home or or driving to pick up my kids or whatever. And so I think, for me, it's education. Part of it is that sense of involvement. What I mean by that is, you know, when I speak to Muslim audiences, I say all the time, look. Muslim mothers are Jewish mothers. You know, there's 4 careers you can have. You can be a doctor. You can be a lawyer. You can be an engineer. You can be a business owner. And there is no, you know, 5th option. You have to be successful. I say to Muslim audiences whenever I'm asked to speak to them, it's like, look, we have enough Muslim doctors and lawyers. We need Muslim writers. We need Muslim storytellers. We need Muslim journalists. You know? If we're not telling our stories, other people are all too eager to tell those stories. And I think, again, that's where and I don't mean to to put the Jewish community up as a model minority community because there's all sorts of problems with that. But I think that's one of the things that the Jewish community really understood from the beginning to say, okay, we got to be in this, you know, and so you look at the the politicians, the fact that we have 3 Muslims in in congress, you're really interested in the true mix. Andre Carson from Indiana, you know, who's African American, Rashida Tlaib, who is a Palestinian, and Ilhan Omer, who is of a Somali background. So really interesting. Again, right there, the African American, the Palestinian Arab, and then the the Somali, the the African African, you know, kind of thing, but lot more than 3 Jewish you know, congresspeople, judges, you know, so so some of it is that level. But then the whole business of I don't mean to say entertainment, but I mean, you know, again, telling the stories and you start to see this like, you know, how many people have a different vision or understanding of Islam because this actor that they know, Mahershala Ali, 2-time Oscar winner, is a a Muslim. You don't follow him because he's a Muslim. You follow him because he's an astonishing actor. But then you've been to his, oh, wait a minute. This guy's a Muslim, and he's a Academy Award winning actor or or this singer or this performer watching the Super Bowl, watching the halftime show, and seeing that magnificent performance, you know, by by Usher and then Alicia Keys. And I'm like, you know, Alicia Keys' husband, Swizz Beatz, that dude's a Muslim. That dude, you know, it's really interesting. And you don't think about, wait, so what does it mean that one of the big producers in rap music is a Muslim? And so we understand things differently if we've got those kinds of examples. Going back to what what I was saying earlier, you know, if the only Muslim you know is Bin Laden, that's that's a terrorist Muslim. What about the Muslims who are doing the kinds of of really powerful work? And and, again, I use an example of someone like Mahershala Ali who happens to be a American Muslim.

Meli [00:39:30]:

Yeah. And, again, I'm hearing a tender balance that maybe our social groups, our religious groups are always trying to balance of the folks who are journalists, actors, politicians who just happen to be versus being identified as a Muslim or a Jew who happens to be a journalist. It seems looking at history, and I know we're here to really kind of talk about the current experience, but what seems to happen is our minority populations get caught up in these stereotypes when we're somehow between the ghettoized community and the so assimilated that people aren't aware that you're a Muslim or a Jew. What what do you think about that idea?

Amir [00:40:29]:

No. I I think that's absolutely the the case, and part of it becomes, you know, it's not just simply to to be a journalist as a Muslim journalist. It's that if you're a Muslim journalist, if you're in the room where the news team is deciding what 6 stories we need to cover today, and you're able to say, hey. You know what? Ramadan starts tomorrow. Well, if if you don't know that Ramadan starts tomorrow, you're not even thinking about, hey. Maybe we should start this. Or, you know, during this kind of a thing, the Muslim community is doing x. You know, if you're just if you're not having access to those kinds of conversations, we just don't know. And so the story that gets put out there is the the story that, you know, folks think will lead and will sell. You know? And so I think part of it is that if you're in that room, you're then able to suggest those stories. I was very fortunate years ago when my last book came out to be on a television program, you know, doing the sort of PR for the book. And one of the people there was Octavia Spencer, your marvelous, marvelous actor who has just done, Hidden Figures. You know, and she talked about when she got that role about how black women did the math to help put John Glenn into space, she thought this is great and this is fiction. Then she realized, no, no, this is real. This really happened like black women did the math to help put a man in space. And she's thinking, look, I'm a black woman. I don't know this story. If I don't know this story, how do I expect someone else to know this story? And so I think that that sense of, you know, how do we tell those kinds of stories? Like, I'd love there to be a documentary about Fazil Rahman Khan, you know, the Bangladeshi structural engineer who made possible the sort of tall buildings in Chicago. So if you look at the Chicago skyline, I think it's not the Willis Tower, I still call it the Sears Tower, the Sears Tower, the John Hancock building, Those buildings are possible because of this Bangladeshi structural new who happens to be a a Muslim. Yet most of us most of us in the Muslim community don't know who that guy was. You know, most Americans don't know who that guy was. And that guy was extraordinary as an engineer. And so I think it's those kinds of things. You know, how do we tell those stories so that we get a sense that these are our kinds of stories? We can make those kinds of connections. I think that's really crucial.

Meli [00:42:47]:

Yeah. And as as they say, do you know her name? Right? Which is which is a good question. Do you know his name? Okay. Amir, we could clearly talk for a long time, and I hope we have another opportunity to have such an engaged conversation. I so appreciate it. Are there, closing words you'd like to say?

Amir [00:43:14]:

No. Just thank you for allowing me the privilege of being on this podcast. I think the work you're doing here is really marvelous. It's an honor to to to be here. And I think, you know, what I do is what my colleagues use education. And if I leave you with one, you know, pithy straight straight statement is, you know, indoctrination is easy. Education is hard. That's what we do here. We educate. We talk about the context. We talk about the complexities rather than saying, here's our side and here's all the arguments, you know, for our side. And so and and I think that this is what gives me hope is is the people who are doing that kind of work, especially people like you with this podcast. So thank you.

Meli [00:43:52]:

Thank you. Well, thank you for coming on my Living Our Beliefs podcast. It's conversations like this that keep me going and keep the whole project to improve coexistence moving forward. Thank you so much. Thank you for listening. If you'd like to get notified when new episodes are released, hit the subscribe button. Questions and comments are welcome and can be sent directly to info@talkingwithgodproject.org. A link is in the show notes. Transcripts are available a few weeks after airing. This podcast is an outgrowth of my Talking with God Project. For more information about that research, including workshop and presentation options, go to my website, www.talkingwithgodproject.org. Thank you so much. Till next time. Bye bye.